Lessons learned from leading Signallers on a large exercise.

While most people are out spending the twilight zone between Christmas and New Years in a state of gluttony and relaxation - myself and 13 of my Signallers were out in Chilliwack B.C. working long hours to provide communications for a Combat Engineering exercise called Paladin Response.

While I'd done this exercise before in 2022 as a Junior Leader (CP Sergeant) --

This year I signed-up to fill the position of the Signal Troop Warrant Officer, and this was probably one of my most impactful and transformative leadership experiences I've had in my Army career.

Context

What is Paladin Response?

Paladin Response is a yearly exercise that's focused on exercising key skills for Combat Engineers such as deploying a variety of bridges and executing river crossings. It brings together over 150+ Combat Engineers (affectionately referred to as "CHIMO's") from all across Canada for 5 days to build on some key skills.

The exercise is mainly split up into three groups - known as ExCon (Exercise Control), PTA (Primary Training Audience - the Combat Engineers) and Support / Enablers (Signallers, Medics, Mechanics, Clerks, Transport). As the name suggests - the main focus is on the PTA to complete their training objectives and "get hands on and lifting bridges".

The Signal Troop operates under the Exercise Deputy Commanding Officer and is charged with providing and maintaining communications for the exercise.

Because the exercised tasks carry with it a lot of risk (i.e. water crossings, boat activities, lifting extremely heavy bridge pieces) - Signal Troop's main job is to ensure communications are up between all parties in the exercise to:

- Respond to any emergences (i.e. if someone gets injured and medics are required), and

- Facilitate the smooth operation of the exercise.

Some of the enablers we supported included the Medics, who were on-site to handle any injuries or incidents.

To fulfill a robust communications plan, Signal Troop must provide the links required to enable a PACE (Primary, Alternate, Contingency, Emergency) plan - which ensures having 4 independent means (or "links") of communciation up so that the right people can send/receive the right information at the right time.

An example of PACE includes:

- Primary - VHF

- Alternate - Satellite

- Contingency - Cellular

- Emergency - Dispatch Rider

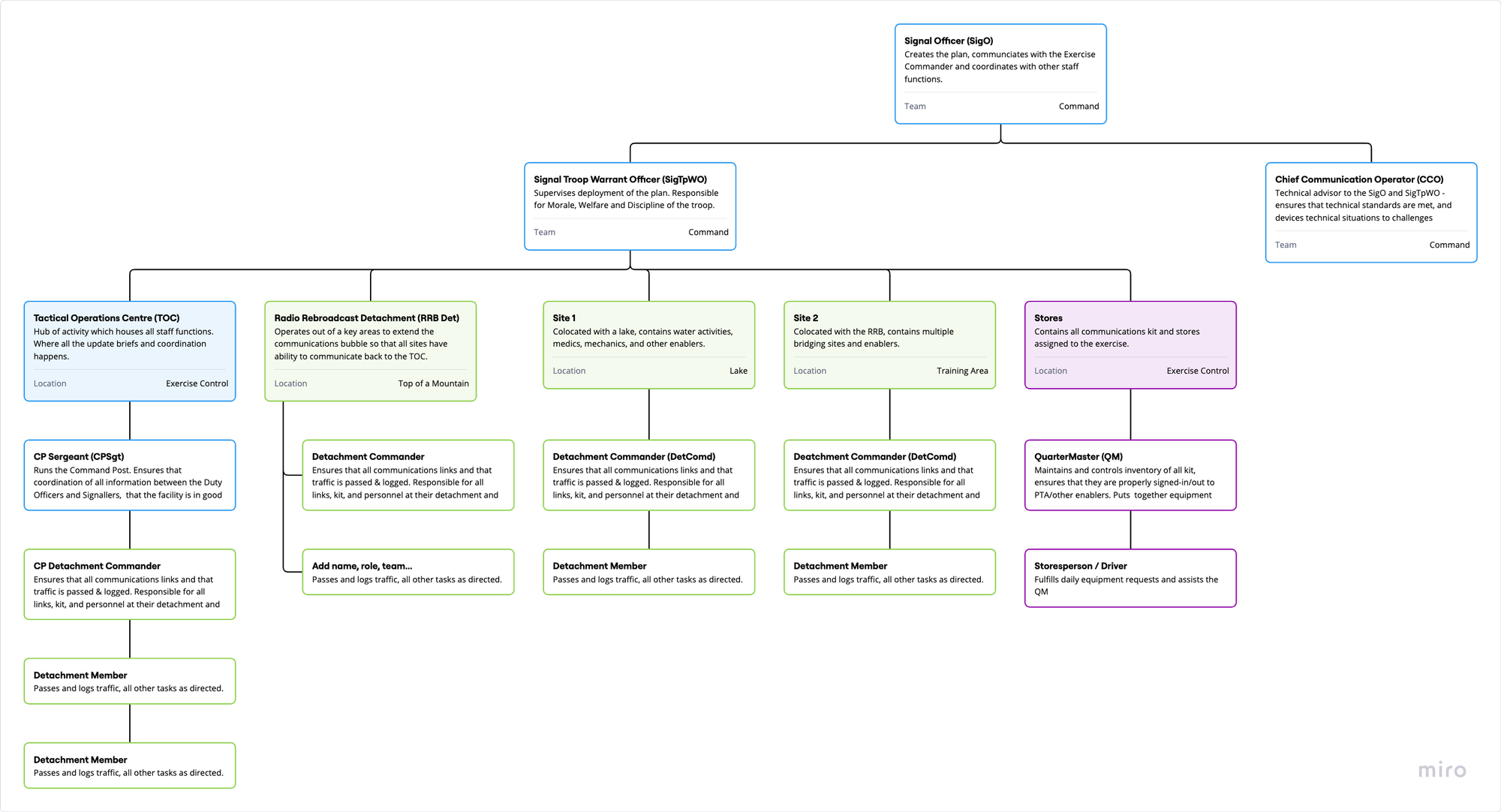

The Signal Troop from the bottom-up consists of Detachments ("Dets") commanded by Corporals who report up to me as the Signal Troop Warrant Officer, and whom are all led by the Signals Officer (SigO). Three specific differences in this org chart are the CP (Command Post) Sergeant who is in charge of the CP Det, the Support Det which consists of the Quartermaster and Storesperson and the CCO (Chief Communication Operator) who doesn't usually come out for this exercise - but was on-site in an advisory capacity.

My Job*

learn-as-you-go event.

As the Signal Troop Warrant Officer - my job revolves around implementing the overall communications plan with an eye on the team. I am responsible for welfare, morale and discipline of the Troop - and act as the middleman to the Signal Officer. I will consolidate requests for support to go up, and will take the feedback and requirements and push them down to achieve the mission.

What does that entail?

- During Pre-Ex Deployment:

- Attending the planning and rehearsal conferences with leadership from all other staff roles

- Assisting and advising the Signal Officer during the creation of their orders;

- Submitting and fulfilling equipment and stores requests

- Coordinating with sub-unit leaders to ensure there was enough time to prep.

- During Deployment: Lead, and implement the Signals plan.

Which..consists of anything and everything that comes up from or for my Signallers. But that's an entire blog post on it's own.

Instead, here are the lessons I learned from that experience.

Lessons Learned

1. Leaders SET CONDITIONS

Fight for understanding & clarity

I didn’t (start off) having a clear understanding of the communications plan; and I didn’t speak up early enough to identify concerns that came up later.

Example

During the planning conferences and rehearsal exercise; there was a concern that we were using too many types of radios at each Det. When I brought this up, I learned that while not technically necessary - it was being prioritized as a redundancy (which is not always a bad thing) based on whether some external groups would have the required radios for interoperability.

Later during the exercise, a lot of my subordinates had the concern that there were too many radios in play - and I didn't have enough understanding of the plan to provide adequate reasoning at the time.

Explanation (Why did this happen?):

- Inexperience - First time in planning conferences (at that scale) & mission rehearsal exercises, combined with being one of the lowest ranks in the room and also having an advisor beside me asking a lot of questions on my part of the puzzle - led to me being reactive and reverting back to my usual level of leadership which comes *after* the overall comms plan has been set, where my job is just execution.

Impact:

- Some concerns I had during the planning phase also popped up again during the execution phase (and multiple times). If I had spoken up then, perhaps those could have been avoided. But more importantly - if I had spoken up and gotten a good answer, then I'd have better answers for my troops.

- A lack of understanding made me reactive to changes as opposed to proactive.

Fix(es) for the future:

- Fight for understanding. Ask more questions. Step on toes. Do whatever’s necessary to get a crystal clear understanding and do not issue a single order or instruction until the overall mission is clear; as this is the best / most stable time to do so.

Fragmentary orders and "More to Follow's" should not be used as a crutch when the time exists to collect more information.

- Mission, Team, Self. Regardless of rank or experience - I’m there to achieve the mission first, take care of my people (to achieve the mission) and lastly look after myself; by being scared to speak up I was working on that order backwards. I was more scared of coming off like I was asking too many questions and wasting time at the planning conferences – which affected the mission and worst: my people. The best thing I can do for the mission in the future, is to speak up.

Lesson:

- As a Troop Warrant, my job is to have the same level of understanding of the plan as the Signal Officer about the plan - but specifically with an eye for staffing. I was too busy working on my technical piece of the puzzle (i.e. getting enough chargers for our new tablets and phones, sorting out the mission feeds for our battle tracking systems) when I should have focused more on the plan to get Det Commanders in to do pre-ex tasks like kit-checks and training.

Leaders Think

(WAIT), Track & Prioritize

2. Leaders THINK - (WAIT) Track & Prioritize

There were too many things coming in and I got overloaded. This led to my troops being jerked around unnecessarily.

Example

On the second day of the exercise, 20 minutes before the morning radio-check (when all callsigns were meant to be established on site), I was met with the following injects:

- One of the trucks broke down and won't start

- The medics radios weren't picked up from our QM and they were already en-route to site.

- One of the new IT systems we'd implemented was having issues.

I reacted to this by informing one of the dets to cross load critical kit into another (smaller vehicle) and head to site, with their additional kit to follow-later while I personally worked on the technical issue.

However, I didn't track that the additional kit had to follow-on later. That kit contained the laptops required for them to have access to e-mail and data on site, which meant that for the rest of the day - they were without a computer and couldn't complete the required Feedback Notes until they returned to site.

Explanation (Why did I do this?)

- I resorted to my usual level of training and comfort. In my usual role (Section Commander), I have enough of an understanding of time, space, complexity within my two dets that I'm able to keep most tasks in my head or action immediately.

- My first reaction is to ACT. “Make a decision” - is what’s drilled into your head at PLQ; but PLQ stab ops missions are not real life.

- On PLQ - everyone had (almost) the same level of training with scenarios that were low in complexity. Taking control during a fire fight or an inject was easier because everyone was on the same level of skill and understanding ( more or less).

- In the real world, and especially in what we were doing - the situations are more complex, and the people all have different levels of training. More care, time and space is needed to prep and issue orders.

- And if a decision is made - more time and space is needed to account for the second and third order effects. Deciding to go “base line left, rapid rate [to prep for taking the trench]” has different follow-on effects than “cross load the comms kit into the second vehicle and split det into two vehicles, roll to site first”.

Impact:

- During peak periods, too many tasks were coming in and some tasks were straight up missed.

- Tasks were not prioritized - orders were issued reactively with little coordination.

- Vicious cycle of catch-up. By the time the tasks became due, it then became a rapid series of status checks, updates and follow-ups to subordinates, which comes off as micromanagement (or "spinning").

- Sub units were constantly reacting to my changes, impeded from getting to a stable / steady state – this reduces morale.

- Lack of prioritization also meant that concurrent activities were not being done efficiently - beause of this, on a couple of nights troops had to spend time additional time *after* coming back for the day to work on tasks that could have been done earlier.

Fix for the future:

- Capture and store. Pluck the tasks out as they come into my ears and make sure they are put onto paper (or whiteboard). Once they’re all in one place I can see the connections, similarities and more effectively prioritize (see next).

- Prioritize the tasks, liaise with higher if necessary.

- Question to myself: Is what needs to happen next an immediate threat to mission success, life or limb? If yes, REACT, if No - WAIT, assess and prioritize.

Lesson Learned:

- At this level, especially when you have 1 or more links downstream in your chain of command - you can’t just keep track of everything in your head and immediately issue out orders.

You're not just a Det Commander anymore. You're in charge of other Det Commanders. Give them the time & space to lead and operate.

If I’m not prioritizing, they’re not prioritizing.

And for them (sub-units), it then feels like “everything’s important, and we’re being penalized for not getting everything done. This is another hit to morale.

3. Leaders Lead

Give direction, get out of the way.

I gave half baked orders, with too many updates, or at the inappropriate times.

Example

On the afternoon of the second day - I directed my QM to complete an ADREP (Equipment Request) run which they had already prepared. Before they left the site, I realized that I forgot to tell the troops to have laptops to complete their Feedback Notes for the next day (which would require a computer); so right before the QM stepped off, I told them to grab some laptops.

Just after they stepped off one of the sites mentioned they needed a power-bar - so I called my QM and got him to come back and grab one. About 20 minutes later, I realized that I would need to get them to the last site in the ADREP route to get the power-bar so that they could have a laptop out to fill out an injury report that had occurred on site to meet the briefing timeline for the afternoon; to which I reacted by calling the QM and asking where they were.

I'm on my way to the sites...like you'd ordered me to...

Was the response, which was then followed up with later in a private conversation:

Rat, you knew where I was and what I was doing. Calling me and asking me to confirm isn't going to change that or make it go any faster.

And they were right!

Explanation (Why did I do this?):

- When tasks were getting missed, my first instinct was to step in and take closer control. This works as a Section Commander leading a Section Attack - but is *not* what is needed when a Det Commander is out there trying to fight your plan.

Impact:

- Dets were occupied waiting for more information to complete their tasks.

- Always more information coming in - constant readjustment. Both myself and subunits occupied waiting for more information instead of completing tasks

Constant adjustment is micromanagement. Make a plan and get out of the way.

If you're always re-adjusting, it teaches your subordinates to wait till the last minute because "it's going to change again later anyways".

Fix:

- Once orders are issued, GET OUT OF THE WAY. Unless there is a change required due to a risk to mission success, life, limb or some other very important reason to necessitate an inject - give your sub units time to react and fight the plan. Failure to do this comes off as micro-management.

Lessons Learned:

- Trust your people. Give orders. Step aside. Take information in from both higher and lower, extract the tasks, then prioritize and issue out the orders at the appropriate times.

- When it’s:

- Multiple sub units (with their own leadership)

- Separated over a larger area (No longer line of sight)

- Delayed in communications

- And All parties* - Doing unfamiliar things (things they haven’t had enough training for recently)

Factor in more time for your subordinates to complete tasks.

4. Leaders FOLLOW-UP

Trust but verify, accountability is essential for learning and growth.

The culmination of all the lessons above: Tasks were missed, but worse - we didn't know that they were missed until it was too late.

Example

On the first day when everyone was rushing to get on site and prove comms - I was constantly hearing back that certain pieces of kit weren't working. It seemed that all 3 dets laptops that they grabbed out of the pile were not booting and apparently some of the radios that I personally tested during pre-ex, were no longer able to Tx or Rx.

I directed my troops to slap N/S (Non serviceable) tags on them and was about to move onto tailoring our ops accordingly (assuming that all laptops were bad) until I was challenged by a supervisor to follow-up. It turned out that only the specific laptops pulled (3 out of the stack) weren't working but the others did; and - the radios did work but they hadn't fitted in the vehicle antenna properly (known as a "finger fault"). If I'd followed up on their reports, we could have had those situations rectified more quickly and the disruption to operations minimized.

Explanation (Why did I do this?)

- I was overloaded, not tracking tasks and prioritizing incorrectly.

- In that moment, the best thing to do seemed to be up and available to respond to all and new tasks, immediately.

Impact:

- Tasks were missed until it was too late.

- Subordinates weren’t effectively communicated their performance, so they weren’t motivated to learn / grow.

Fix:

- In the future when I'm maintaining a log of all tasks; make sure that the tasks are not considered "completed" until I have followed up.

Lessons Learned:

No News is Good News is a bad example. While we expect our troops to complete all orders as a norm - it's my responsibility as a leader to follow-up not just for ensuring completion, but also to assess their performance and provide feedback.

There were times on the exercise where I felt I was just being the "bad guy" beause I had to tell them when things weren't being done well. Providing corrective feedback is part of the job - but providing feedback without the time or opportunity to implement them can be almost as bad as no feedback at all.

Conclusion

Comms are green, sir.

Over the 5 days we had comms up, and all traffic was passed. When I look at my set of orders we completed the mission and my team performed well, receiveing many accolades from both the PTA and members of Excon. I'm proud of the work my Signallers did and it was a pleasure to lead them.

However, this was definitely a "gut-check" experience. It wasn't my best performance and the experiences taught me a lot of what I need to work on. I do feel guilty that at times, my troops were affected by my decisions, but experiencing and practicing different leadership styles are actually a huge benefit of being in this organization. Armed with this knowledge; I know what I'm going to differently when I'm in this role for the next time - and I'm thankful for my subordinates, and my supervisors.

JIMMY! ⚡️ 📡